In 1889, London fell in love with a hunky weightlifter named Eugen Sandow.

A German Jew born in the country then known as Prussia, Sandow made his British on-stage debut at the London Aquarium where he smashed through a series of increasingly tough strongman challenges. Later that year, he sold out a run of performances at the Alhambra Theater, armed with a new signature show-off move: the “Tomb of Hercules,” which involved balancing a board stacked with weights and, incredibly, his manager, on his knees and shoulders.

Before long, Sandow had sparked a global craze for so-called “physical culture.” The world’s first bodybuilding contest was held in 1891; shortly afterwards, Sandow toured the U.S. and won legions of new fans with his ultra-ripped physique and macho challenges — like wrestling an elderly lion.

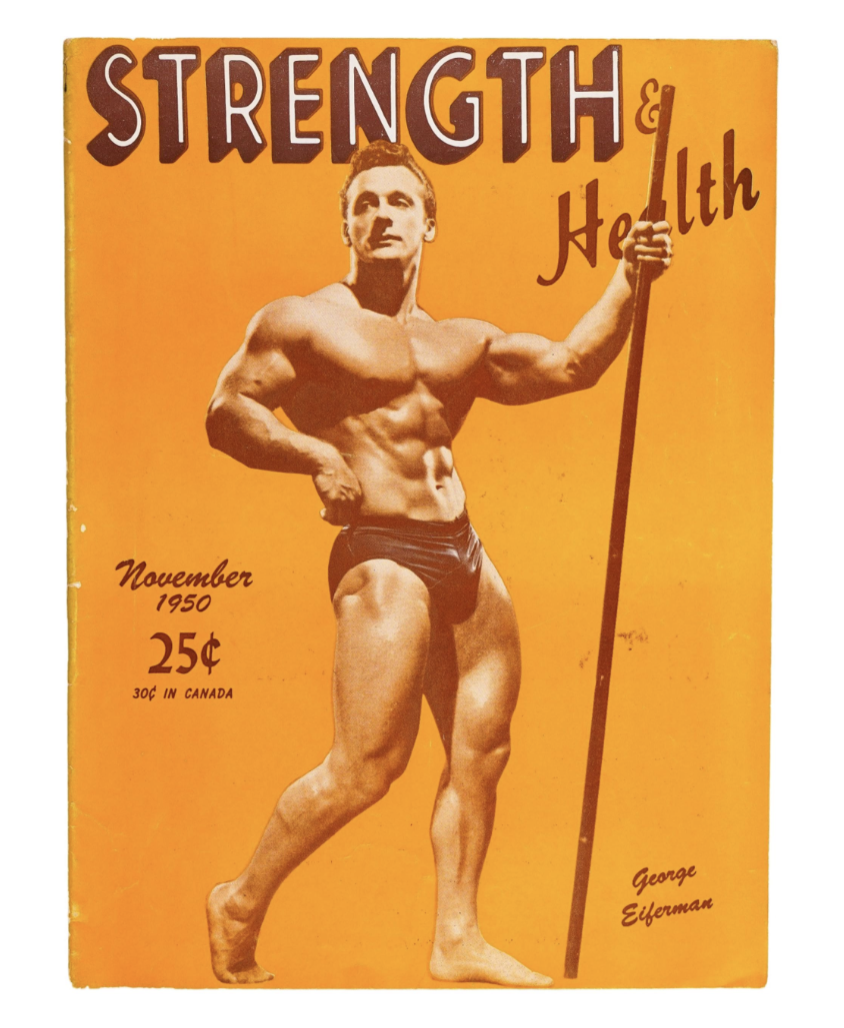

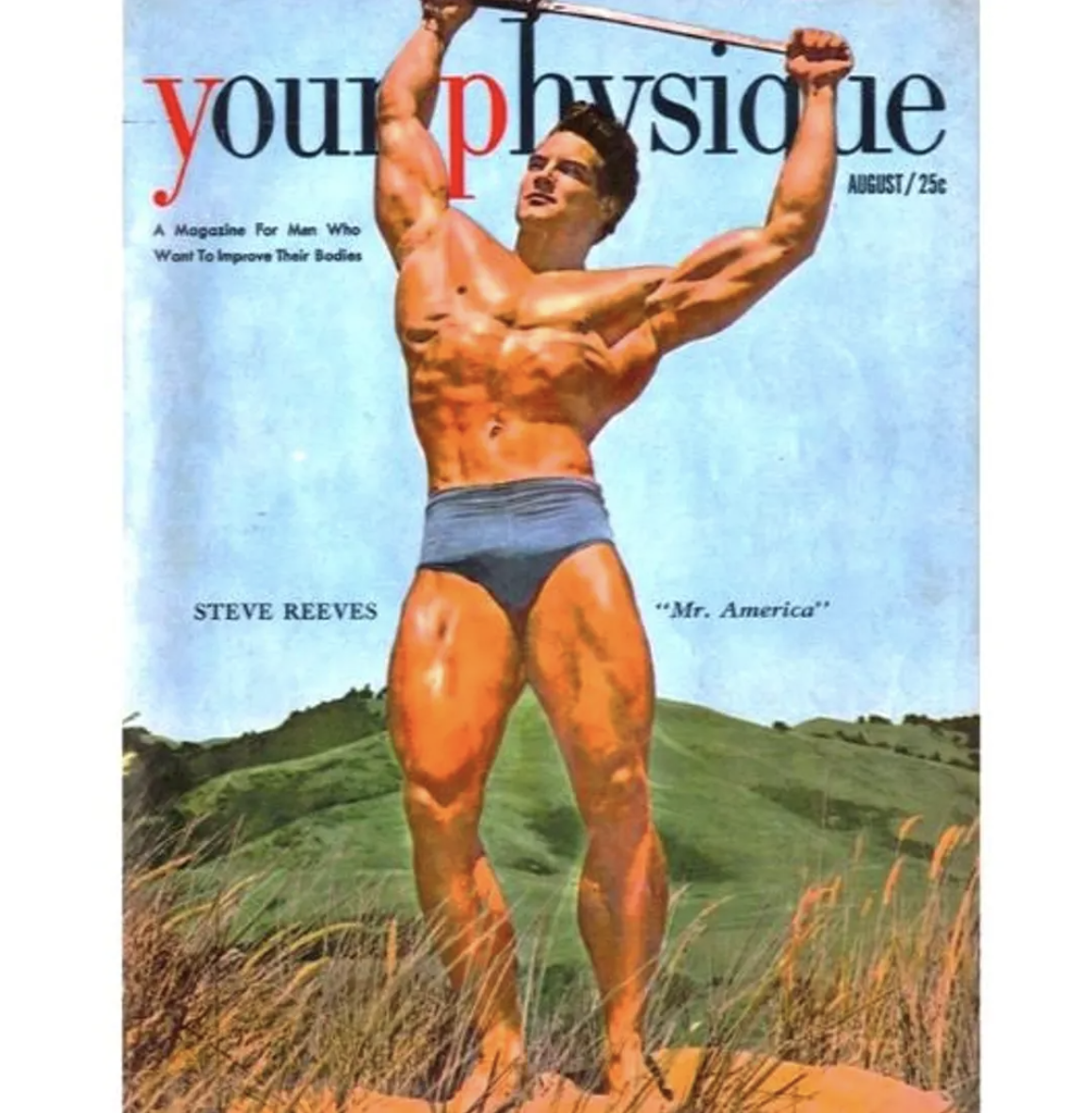

A slew of magazines, led by Sandow himself, soon emerged to capture the glistening physiques of these strongmen. Sandow’s own 1898 Magazine of Physical Culture is credited as the world’s first bodybuilding magazine, but copycat publications kept cropping up throughout the early 20th century. Between their pages, guys flexed their biceps in increasingly-skimpy underwear — their dicks barely covered by snug posing pouches. They were widely-read, and advertised primarily to physique-conscious bodybuilders and budding strongmen looking for health tips.

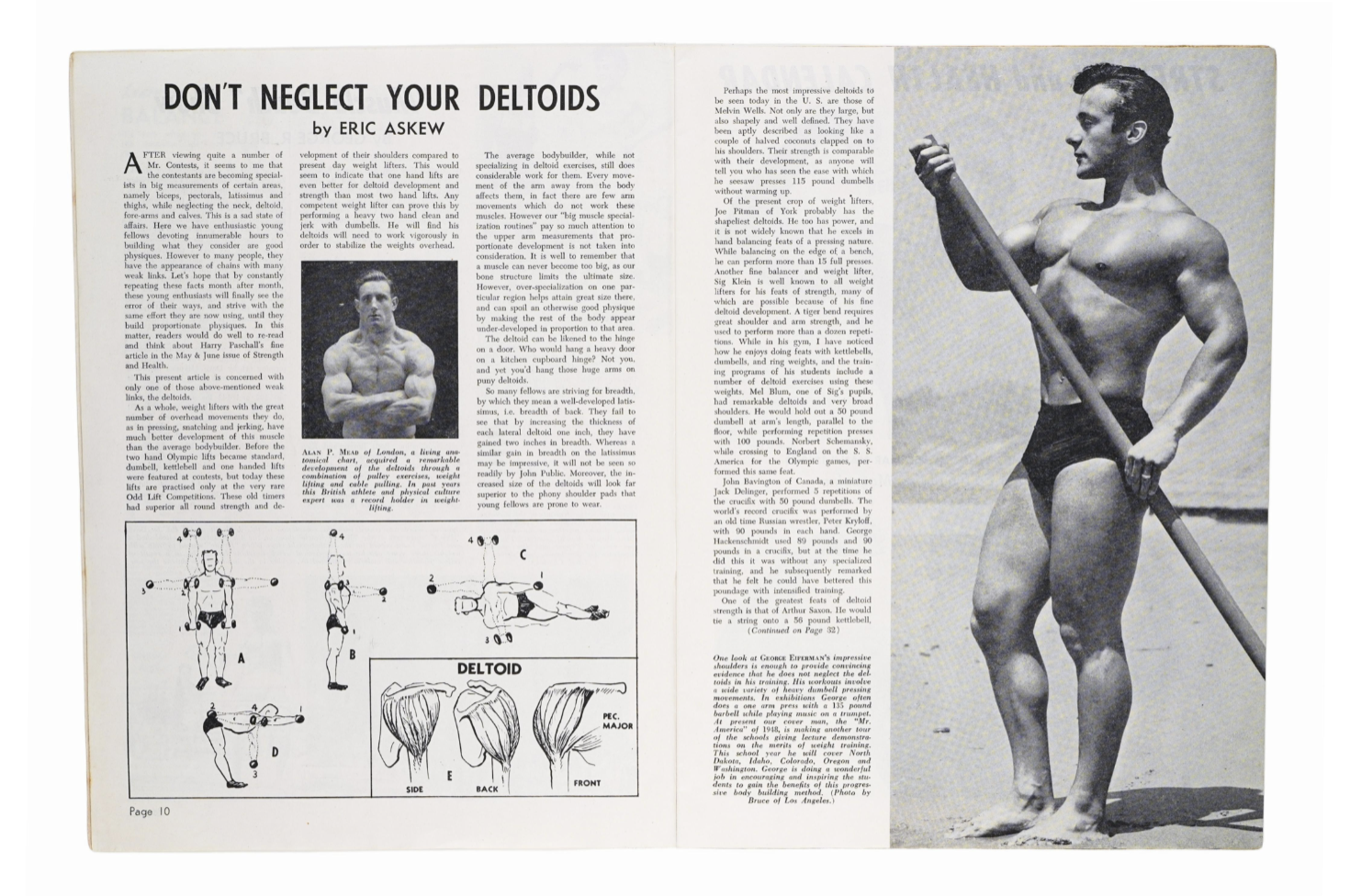

But in retrospect, it’s not hard to see how even these early bodybuilding magazines could become jerk-off material in the right hands. Sandow himself showed off his glutes in skimpy, leopard-print briefs, planting a tender kiss on his hulking bicep. It wasn’t until the 1930s and 1940s, though, that things got more risqué — a gradual shift aided by the rise of gay photographers like Bob Mizer. Briefs became thongs, and magazines like Strength & Health ran ads in their back pages for the purchase of Mizer’s “undraped” naked photographs. These magazines were suddenly hella gay, and yet completely unwilling to acknowledge it.

Meanwhile, Hollywood directors were forced to stay within the confines of the ultra-rigid Hays Code, which barred pretty much any homosexuality or nudity on-screen. And so, these hints of homoeroticism were radical at the time, and their gay readership was seen as a sort of open secret. “When you look at the historical record and what people actually said about these magazines at the time, everybody knew they were gay,” laughs David K. Johnson, author of Buying Gay: How Physique Entrepreneurs Sparked A Movement. “Art historians and cultural critics said they didn’t know if they were gay, who bought these magazines and who produced them. But customers certainly knew.”

1951 marked a full-blown shift from “bodybuilding magazines” to “physique magazines,” led by Bob Mizer and his Physique Pictorial. “Mizer launched that magazine specifically because he was being forced out of the mainstream alternatives,” explains Johnson. “He was taking pictures and advertising in the back of them, but his images were considered too risqué. They were nudes, or nearly nudes. Editors were telling him to tone it down, so he was like, ‘Okay, I’ll form my own legacy.’” It was a controversial move. In fact, Strength & Health — one of Mizer’s regular clients — published an essay, “Let Me Tell You A Fairy Tale,” which took jabs at him, blasting “homosexual magazines” and their “corrupting influence on youth.”

Presumably, the weightlifting world now had some inclination that “physique culture” came with a horny gay fanbase. These were pre-porn days; you couldn’t simply click a few buttons and be presented with a full-frontal nude of a lubed-up guy. Everyone knew gay men existed, but criminalization loomed large for those who cruised or were open about their sexuality. Even when Mizer launched Physique Pictorial, he spoke of his desired customer base euphemistically. “I think they were called ‘physique enthusiasts,’” Johnson tells me.

Still, it didn’t take long for gay buyers to clock this new publication. “They knew these were different to the regular bodybuilding magazines,” Johnson continues. “Postal censors were also aware that these were gay magazines trying to solicit a gay market, and they went after them because of it. But they weren’t showing any more skin than the regular bodybuilding magazines, or than Playboy. They weren’t technically obscene, but they were considered obscene because they were images of men being viewed by men.”

Editors of conventional bodybuilding mags were similarly pissed. They proclaimed their disgust at the rise of gay magazines, but Johnson adds that they were also pretty angry about losing a key chunk of their demographic. Legal attacks ensued. “Prosecutors said that physique magazines were promoting homosexuality in American society. Well, they were right,” he laughs. “These gay consumers could suddenly see that their desires were shared by thousands of other people.”

Physical culture was never supposed to be gay. Sandow launched his magazine to document his own splendor and profit from his muscle-hungry acolytes, sparking a full-blown industry along the way. Early bodybuilding magazines borrowed his formula, placing oiled-up muscle dudes front and center (apparently without understanding their role in fulfilling the desire of gay consumers across the country). 1930s publications like Strength & Health profited from the homoerotic work of gay photographers, but feigned ignorance when their prized publication built a huge gay fanbase.

Mizer called their bluff, turning Physique Pictorial into a beloved institution and a touchstone of gay history. Later physique magazines like Mars and Grecian Guild built on this phenomenon, with artists like Tom of Finland turning the hyper-ripped archetype into salacious artworks of macho guys with massive schlongs. And although physique magazines waned after full-frontal nudes were officially permitted in the late 1960s (Physique Pictorial, of course, printed uncensored cocks in the years afterwards), they live on in the hearts and browser search histories of gay men today.

1 Comments